In COSMOS (2019), three astronomers are amazed when the newest member of their team catches radio signals of a potentially alien origin. This film of first contact was surprisingly fun if severely clunky due to its limitations.

A first feature made without any budget, COSMOS pulls off its intention with a simple, bare bones setup, a lot of heart, and some heavy borrowing from Stephen Spielberg’s directorial style. The film begins with two scientists and an engineer driving to a remote location in the woods, where they can view the heavens. Each has a different project he’s working on either personally or as a job. There’s some friction between the three, as two of them had a previous falling out, and the third is a newcomer to the group.

All night, they sit in a car manning their equipment, which honestly for us nerds out here is fun to watch, and then Mike, the new guy, catches a seemingly impossible radio signal. On a lark, he radios back, and then, again impossibly, gets a response in a short time. Suddenly, the three men realize they might actually be looking at a first contact possibility. With numerous ups and downs, they work out their issues and work together to capture this history-making communication.

There’s a lot to like here: the likeable characters (particularly Mike and the actor playing him, who does a lot of the heavy lifting), the nerdy astronomy equipment, the realistic process of trying to figure out what they’re listening to and what it means. The film has some first-film issues, though. The first contact is fun but not as exciting as in, say, the film CONTACT, which admittedly set a pretty high bar for this sort of thing; the men are so slow to realize what they’re dealing with that while very realistic, it drains some of the catharsis out of it. Another issue is the resolution of the interpersonal conflicts, which is delivered with dialog that is overly emotionally precise, a lot of exposition, and heavy-handed music and camera shots borrowed from Spielberg. The last issue is the climax is built on a long string of ridiculous things going wrong.

These things kept me from loving it, but I liked it a ton for what it is, which is a simple, realistic take on how first contact might be achieved.

In the sci-fi series RAISED BY WOLVES (HBO), two androids are sent to a wild planet to start a new civilization after religious wars turn Earth into a dying planet. I loved this one, though it could have been shorter, and it ends on a PROMETHEUS-style note that left me a little wanting.

In the sci-fi series RAISED BY WOLVES (HBO), two androids are sent to a wild planet to start a new civilization after religious wars turn Earth into a dying planet. I loved this one, though it could have been shorter, and it ends on a PROMETHEUS-style note that left me a little wanting. THE RULES OF THE ROAD by C.B. Jones invents an engaging urban legend and then brings it to life in a horror read that gives Creepypasta a run for its money. I liked this one quite a bit.

THE RULES OF THE ROAD by C.B. Jones invents an engaging urban legend and then brings it to life in a horror read that gives Creepypasta a run for its money. I liked this one quite a bit.

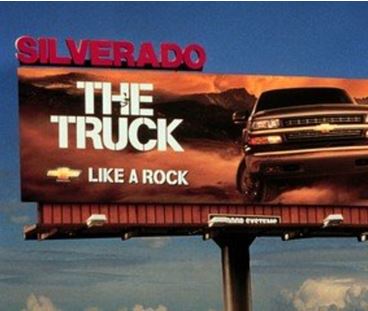

The first bit of advice is obvious, which is to avoid mixing metaphors and similes in proximity in the text. And to avoid mixing incongruous metaphors, and mixing similes together. You can write, “This truck is a rock, it forges ahead no matter what,” and the reader will understand the meaning of the sum, but it just doesn’t sound right because the individual ideas don’t mesh in a congruent way. In dialogue, of course, you can do anything if it serves the character, but in narrative, not so much. Personally, I subscribe to the theory that the best writing goes unnoticed so that the reader becomes more immersed in the story. If you’re going to call attention to your writing, however, you always want the reader to go, “Nice,” rather than, “Oh, that’s right, I’m reading a book.” For me, that’s my primary guide.

The first bit of advice is obvious, which is to avoid mixing metaphors and similes in proximity in the text. And to avoid mixing incongruous metaphors, and mixing similes together. You can write, “This truck is a rock, it forges ahead no matter what,” and the reader will understand the meaning of the sum, but it just doesn’t sound right because the individual ideas don’t mesh in a congruent way. In dialogue, of course, you can do anything if it serves the character, but in narrative, not so much. Personally, I subscribe to the theory that the best writing goes unnoticed so that the reader becomes more immersed in the story. If you’re going to call attention to your writing, however, you always want the reader to go, “Nice,” rather than, “Oh, that’s right, I’m reading a book.” For me, that’s my primary guide.

SYMBOLISM

SYMBOLISM

For example, in ARRIVAL, both the story structure and the alien language are circular, showing how everything is connected and how time can be manipulated so that everything is happening at once. This idea expands in the viewer’s mind as the story reaches its conclusion. Even the protagonist’s daughter’s name, Hannah, is symbolic, as it’s a palindrome.

For example, in ARRIVAL, both the story structure and the alien language are circular, showing how everything is connected and how time can be manipulated so that everything is happening at once. This idea expands in the viewer’s mind as the story reaches its conclusion. Even the protagonist’s daughter’s name, Hannah, is symbolic, as it’s a palindrome. In THE SIXTH SENSE, the color red shows up as a motif, representing anything connected to the spirit world, particularly a certain doorknob for a certain door that is always locked, as it leads to a room where the protagonist will learn his true nature. In GROUNDHOG DAY, the groundhog is a motif representing the protagonist repeating the same day over and over. And in THE HUNGER GAMES, the mockingjay is an accidental creation of the ruling regime that symbolizes the ability to survive in any environment and becomes the symbol of rebellion.

In THE SIXTH SENSE, the color red shows up as a motif, representing anything connected to the spirit world, particularly a certain doorknob for a certain door that is always locked, as it leads to a room where the protagonist will learn his true nature. In GROUNDHOG DAY, the groundhog is a motif representing the protagonist repeating the same day over and over. And in THE HUNGER GAMES, the mockingjay is an accidental creation of the ruling regime that symbolizes the ability to survive in any environment and becomes the symbol of rebellion. Leitmotif

Leitmotif My first book for a Big 5 publisher was a vampire novel. The plot was a plague kills the world’s children only to bring them back as vampires. Their parents need to get them blood so they can continue surviving. The kids are vampires, but the parents in the book are the monsters, willing to do whatever it takes to keep their kids alive.

My first book for a Big 5 publisher was a vampire novel. The plot was a plague kills the world’s children only to bring them back as vampires. Their parents need to get them blood so they can continue surviving. The kids are vampires, but the parents in the book are the monsters, willing to do whatever it takes to keep their kids alive.

One way to express theme is by giving the protagonist a moral choice. In THE MALTESE FALCON, detective Sam Spade is given a clear choice of love and money versus honor and justice and chooses honor and justice, thereby thematically stating they are more important.

One way to express theme is by giving the protagonist a moral choice. In THE MALTESE FALCON, detective Sam Spade is given a clear choice of love and money versus honor and justice and chooses honor and justice, thereby thematically stating they are more important.